The quickening of life due to technology is a blessing I depend on daily. But it is also a curse at times, especially at the end of the semester when it comes to grades. I submitted my fall grades today at 11:45am (they were due at noon!). By 4pm the first grade complaint had arrived in my email. No more waiting a week for the printed report card to show up in the mail or having weeks before the start of the next semester for the student to cool off before being in touch!

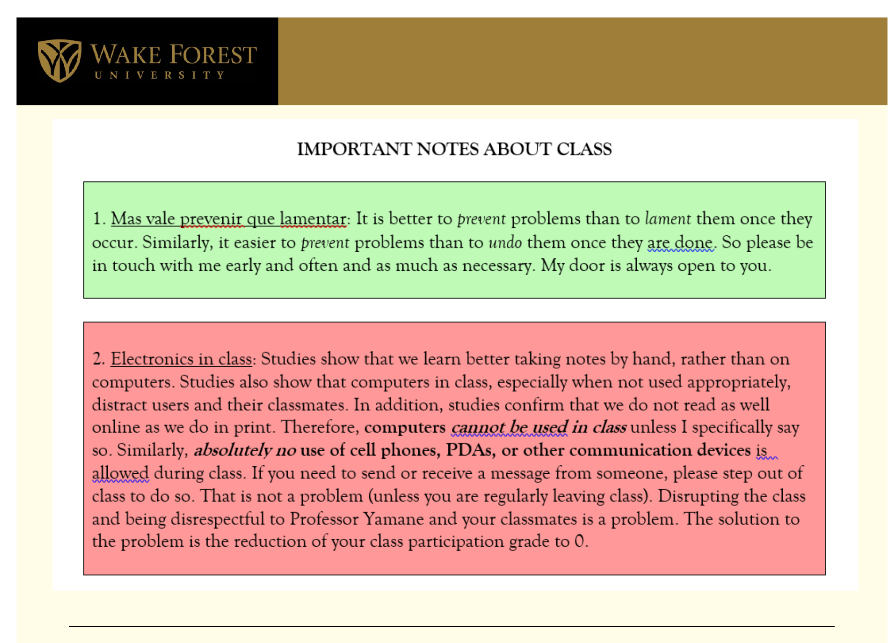

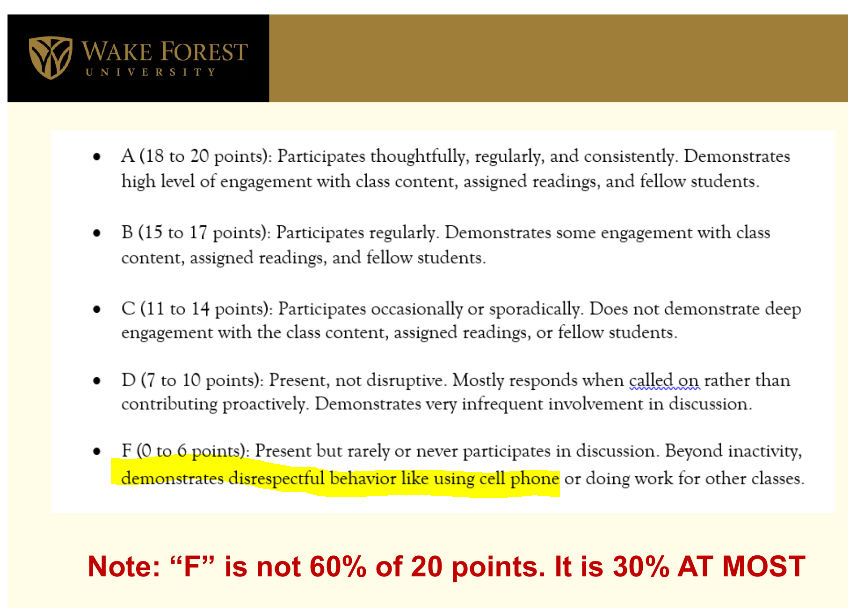

I never worry about “getting in trouble” for the grades I give. My syllabus is usually a dozen pages long, reading like the legal document that it has become, spelling everything out in meticulous detail. I also use grading rubrics handed out in advance so students know the grading criteria for individual assignments.

I never worry about “getting in trouble” for the grades I give. My syllabus is usually a dozen pages long, reading like the legal document that it has become, spelling everything out in meticulous detail. I also use grading rubrics handed out in advance so students know the grading criteria for individual assignments.

I don’t even get frustrated by the grade complaints. What I mostly get is sad. I feel badly that they are under so much pressure to get certain grades, whether the pressure if from their parents or themselves.

I feel especially badly for students who invest so much of their sense of self in their grades that they see an “A-” and they do not experience happiness. They only see what is not there.

Or, worse, they have a sense that if they do their best, that it must be worth an “A.” They do not understand a world in which THEIR best does not equal THE best.

Case in point, a very good student I had in class this semester saw an “A-” only for what was not there, rather than what was there. S/he wrote to me:

I’ve never had a professor say that an A is a 95 or above which is why I’m concerned about this because I worked incredibly hard in this class and feel like I deserve an A and to any other professor I have ever had at wake a 94 would be an A.

So if you could provide me with clarity on why you choose to grade this way and why it isn’t standardized across classes that would be helpful because I am concerned about this.

My response:

I am happy to clarify, though I doubt given your state of mind about this that this is going to make you feel any better. But hopefully I can give you both some information and some perspective (my view at least) on the grading in general and your grade in particular.

The syllabus, which I reviewed at length at the beginning of class, specified the following grades according to points earned:

“The scale for grades based on the number of points earned over the course of the semester is as follows:

A 96‑100

A‑ 92‑95

B+ 89‑91

B 86‑88

B‑ 82‑85

C+ 79‑81

C 76‑78

C‑ 72‑75

D+ 69-71

D 66-68

F Less than 65”

So, in fact, 96 and above is an A in this course (and all of my courses).

The bulletin of Wake Forest College (p. 33) specifies only that A represents exceptionally high achievement, A-, B+, and B represent superior achievement, B-, C+, and C represent satisfactory achievement, C-, D+, D, and D- represent passing but unsatisfactory performance, and F is failure. There are no instructions nor is there any standardization in grading within or between departments beyond these broad frameworks.

So, although you may have never had a professor say that a 95 (or a 96) represents an “A”, it is certainly the case that professors grade very differently. In some cases most students get A’s and in other cases few students do. In some classes (accounting, biology, math) many students fail, and in some (com, soc, religion) none do. So, grading varies enormously from class to class, such that what a 94 means in one class — and what it take to earn a 94 — is not the same in another class.

I am very sorry that you do not feel that being at the high end of “superior” is adequate. I wish that you would look at an A- and think, “Awesome, I performed at a superior level.”

I am also sorry that you feel if you work incredibly hard that you “deserve” an A. It is absolutely possible for people — myself included — to work incredibly hard an not attain “exceptionally high achievement,” a grade that is reserved — in my class, at least — for truly exceptional (rare, unprecedented, extraordinary, remarkable, phenomenal — some synonyms) work. Your work was at the high end of superior, and in the case of your class participation, it was exceptional — hence your getting 100% of that component.

You have probably already figured this out, but for the record let me put this in some perspective for you. If you take 120 credits to graduate from Wake Forest, you will have the opportunity to earn 480 grade points. For this 3 credit course, the difference between an A (4.00) and an A- (3.667) is 0.999 grade points (p. 33 of bulletin). Or, in the context of your college career, 0.2% of your total grade points.

As I said at the outset, I am sure that nothing short of “ooops, I made a mistake, you get an A” will put a smile on your face and give you a sense of satisfaction in a job well done. But that is my hope for you.