Having discussed my “discovery” of the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, as well as a brief history and mention of my pilgrimage to the Manzanar internment camp, I now want to consider conflicting attitudes of Japanese-American detainees.

(Note: Documents referenced below are part of what used to be called the Barnhart Catalog of Japanese Evacuation and Resettlement Documents at UC-Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, a repository for a large number of primary documents from the period. I originally reviewed these physical documents back in 1989; some I have been able to find online, where linked below. Others I could not find due to reorganization of the files prior to digitization.)

Under the pressure of evacuation and detention, two distinct attitudes toward the government relocation program developed. On the one hand, there were those who advocated cooperation with the government. They tended to side with the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), a Nisei organization which came to be the liaison between the government and Japanese detainees.

Not all detainees, however, felt they owed the government their cooperation nor, for some, their allegiance. Resentment toward the evacuation and detention of US citizens and loyal resident aliens was central to this view of the situation. Many, though not all, who held this view were vehemently opposed to the JACL, its beliefs and its followers.

Pro-JACL Detainees

The Pro-JACL detainees recognized the injustice which they had suffered, but were always more concerned with the image that Japanese-Americans portrayed to the American public. They felt resistance or lack of cooperation would be a black mark on the record of Japanese in America and would be seen by whites as justification of the evacuation and detention. Clarence Nishizu, detained at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, argued that to “pave the way for the rest who are in the center, it is the responsibility of the Nisei to create the most favorable impression upon the public” (Opinions of Evacuees, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M4.00, p. 19).

Another Nisei reflected, “Since things Japanese did were unpopular. the Nisei went out whole hog for things American. They became 200% flag waving ‘Americans'” (Michio Kunitani, Tanforan Politics, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B8.29, p. 15).

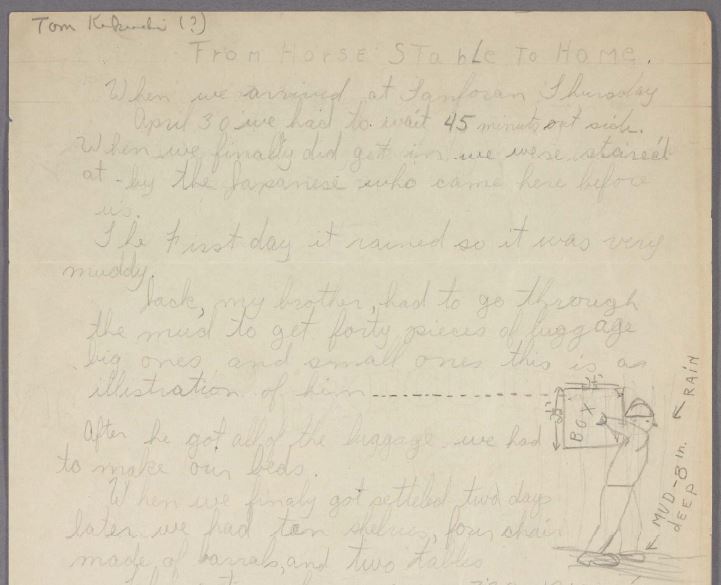

These detainees always sought to prove their loyalty to the United States: in being detained, they were just doing their part in the war effort. One high school junior expressed this attitude very clearly and concisely: “Many men have given their lives for their country since December 7. They gave their all for their native land. Let us drop our ill feelings and take on this life in camp as our duty in this war as loyal Americans. ” Several essays written in class at Tanforan (detention center) High School express the feeling toward the relocation (see My Role in Relocation, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B 8.32, Barnhart Catalog).

The Pro-JACL detainees looked forward to reintegration (and even assimilation) into society after the war ended, and wanted to be able to fall back on their cooperation during the war to ease that process.

Anti-JACL Detainees

The Anti-JACL detainees resented the hypocrisy of a supposedly democratic government that would detain its citizens without due process of law. One Nisei wrote in a letter to friends, “After being taught and educated that freedom of expression and movement is something worth while . . . , it is extremely difficult to accept cooping up as if it were [the] inevitable hand of fate [that] had thrust us here, and that we should meekly accept that as such” They resented being asked to prove their loyalty to America: “the whole thing and the attitude of the people outside toward us (prisoners of war) gripes me. What the hell. They take us out of our paths of life and put us in a rat-hole like this and expect us to be contented. Who do they think we are anyway?” (Correspondence from Tanforan Assembly Center, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B 12.50, Barnhart Catalog).

And they resented the life in the relocation centers: “Minidoka [Relocation Center in Hunt, Idaho] is a lonely place, spiritually bleak, devoid of hope and warmth. It is surrounded by barbed wire, and watch towers punctuate the horizon . The only gate is guarded by military police. No one enters or leaves without credentials” (R.M. Hosokawa. A Phi Beta Kappa Nisei Speaks, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder 8.50.

For most of the detention, the Pro-JACL attitude was dominant, and the centers were without significant disturbances. The prevailing attitude was one of cooperation. All along, there existed underground organization s coordinated by Anti-JACL detainees. But, for the most part, they were unable to mount any significant collective resistance to the centers’ administrations.

Not only did they contend with the Pro-JACL factions for ideological and material support, but they were also up against a wartime state organization, the War Relocation Authority, that had the full coercive force of the US Army to back it up. (The WRA was a civilian agency established to administer the relocation and detention centers by Executive Order No. 9102, March 18, 1942, see Appendix C in Myer, Uprooted Americans, p. 309, for the full text of the order.)

Add to that the barrage of pro-American propaganda leveled upon the detainees (reading the essays and school newspapers of the high school students is remarkable evidence of this type of ideological indoctrination) and clearly the formation of a resistance movement would seem unlikely.

During the detention, however, the US government instituted a policy which was the spark needed to ignite the fire of latent antipathy among the detainees. In my next post I turn to that “critical incident” and the collective resistance unleashed.